Your Eyes, Our Passion

Retinal Detachment

Retinal detachment is the separation of the retina from the underlying choroid. This results in a profound loss of vision and requires major surgery to re-attach it.

RETINAL DETACHMENT AND RETINAL TEARS

Retinal detachment and related vitreous problems affect one out of every 10,000 people each year. It is a sight-threatening eye problem that may occur at any age although it usually occurs in middle-aged or older individuals. Surgery is often beneficial, and if done in time, can restore good vision. At Shroff Eye Centre, we have a dedicated team of Vitreo-Retinal specialists committed to providing you with the best possible care to protect your vision.

What causes retinal detachment?

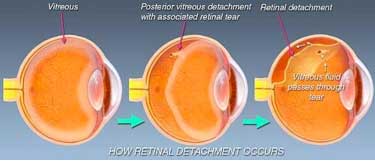

Most retinal detachments are caused by the presence of one or more tears or holes in the retina. Normal aging can sometimes cause the retina to thin and develop holes, but more often these are caused by shrinkage of the vitreous body (posterior vitreous detachment).

The vitreous is firmly attached to the retina in several places around the back wall of the eye. As the vitreous shrinks with aging, it may pull a piece of the retina with it, leaving a tear or hole in the retina. Fluid from the vitreous body then passes through the retinal tear detaching the retina from its normal position (retinal detachment).

Posterior vitreous detachment (vitreous separation from the retina) is a natural process of aging and usually does not lead to any damage to the retina. It is, however, more common and occurs earlier in people who: –

- Are abnormally nearsighted (high myopia);

- Have undergone cataract operations (aphakics);

- Have had YAG laser surgery of the eye;

- Have had inflammation inside the eye

It should be noted that there are some retinal detachments that are caused by other diseases of the eye such as tumors, severe inflammations, or complications of diabetes. These so-called secondary detachments do not have tears or holes in the retina and treatment of the disease that caused the retinal detachment is the only treatment that may allow the retina to return to its normal position.

How is a person to know of the presence of retinal weakness, holes or tears?

In some patients, the formation of a retinal tear is preceded by flashes of light, which are indicative of pull (traction) on the retina. In others, the tear may break a small blood vessel in its path causing a small hemorrhage (bleeding), with the blurring of vision and ‘floaters’.

However, in the majority, retinal holes are completely asymptomatic, as they usually occur in the periphery of the retina and not in the visually important central part. They, therefore, do not cause any visual problem at all, unless they have led on to a retinal detachment. At this stage, profound loss of vision or field occurs.

It should also be noted that ‘floaters’ are very commonly seen by people who have no eye disease. They are seen as small specks, circles, lines, clouds or cobwebs moving in one’s field of vision. They are actually tiny clumps of gel or cells inside the vitreous and cause no harm.

A routine examination by binocular indirect ophthalmoscopy by a person proficient in this method is the only way holes or tears may be detected before they can cause retinal detachment.

What can be done about floaters?

Floaters can get in the way of clear vision, which may be annoying when you are trying to read. You can try moving your eyes; looking up and then looking down to move the floaters out of the way. While some floaters may remain in your vision, many of them will fade over time and become less bothersome. However, you should visit your ophthalmologist if you suddenly notice new floaters because you need to know if your retina is torn.

What causes flashing lights?

When the vitreous gel rubs or pulls on the retina, you may see flashing lights or “lightning streaks”. If you notice the sudden appearance of light flashes, you should visit your ophthalmologist immediately to see if your retina has been torn.

Who runs a greater risk of developing such a problem?

People more prone to developing retinal degeneration, holes, and tears, and subsequent retinal detachment are myopes (nearsighted persons), aphakics (people who have undergone cataract surgery), those with a family history of retinal detachment and people with symptoms like light flashes and onset of a large number of floaters.

These groups of patients must undergo regular and thorough retinal examination by indirect ophthalmoscopy.

How can retinal detachment be prevented?

A careful examination of your retina binocular indirect ophthalmoscopy as mentioned above will be done. For this procedure, your pupils will be dilated with eye drops. During this painless examination, your ophthalmologist will carefully observe your retina and vitreous and look for holes and weak areas. At this stage (i.e. retinal detachment has not yet occurred), they can easily be closed or sealed by producing minute scars in the retina around them, which “weld” the retina to the choroid and prevent fluid from seeping through the hole. These scars can be produced by the heat of a strong light source (laser photocoagulation), or by controlled freezing (cryotherapy). Which of these two modalities is chosen, depends on the location of the hole and the presence or absence of cataract and vitreous hemorrhage, and the retinal surgeon decides individually for each case after a thorough examination. Both cryotherapy and photocoagulation are usually carried out as an outpatient procedure. As the treatment is from the surface of the eye, no invasive surgery is involved.

Symptoms of retinal detachment

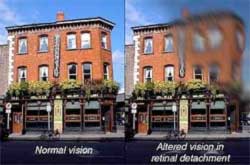

Some retinal detachments may begin without noticeable floaters or light flashes. In those instances, patients may notice a wavy or watery quality in their overall vision or the appearance of a dark shadow in some part of their side vision. Further development of the retinal detachment will blur central vision and create the significant loss of sight in the eye unless the detachment is repaired.

A few detachments may occur suddenly and the patient may experience a total loss of vision in one eye. Similar rapid loss of vision may also be caused by bleeding into the vitreous when the retina is torn.

Detection & diagnosis

A detached retina cannot be viewed from the outside of the eye. Therefore, if the above symptoms are noticed, an ophthalmologist should be visited as soon as possible. Again, binocular indirect ophthalmoscopy through dilated pupils is essential to thoroughly examine the retina. Other special instruments including contact lenses, slit lamp and ultrasound may also be used.

Treating retinal detachment:

If the retina has become detached and the detachment is too large for laser treatment or cryotherapy alone, surgery is necessary to “re-attach” the retina. Without some type of retinal re-attachment surgery, vision will almost always be lost.

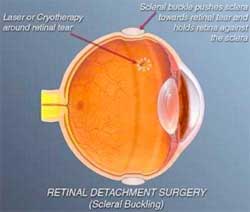

Scleral Buckling

The traditional surgery for retinal detachment is scleral buckling and is performed in the operation room under local or general anesthesia. In this process, after cryotherapy is done to seal the retinal tears, a piece of silicone plastic is sewn onto the outside wall of the eye (sclera) over the site of the tear. This pushes (buckles) the sclera in toward the retinal tear and holds the retina against the sclera until scarring from the cryotherapy seals the tear. This procedure is usually combined with placement of an encircling silicone band around the circumference of the eye to lessen the pulling of the vitreous on the retina. The surgeon may also drain fluid from underneath the retina and place a gas or air bubble into the vitreous cavity. These buckles and bands are left permanently and are not visible from outside. Success rates for re-attaching the retina with scleral buckling are approximately 90-95%.

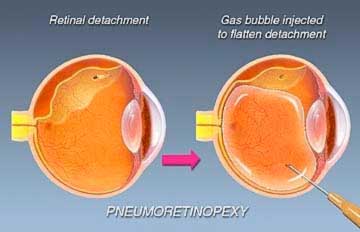

This is another type of surgery for re-attaching the retina. Instead of placing a buckle after cryotherapy, the surgeon injects a gas bubble inside the vitreous cavity of the eye. The patient is instructed to keep his or her head in a specific position so that the gas bubble seals the retina tear by its surface tension effect. Circulation of fluid through the tear stops and the retina is re-attached.

Vitrectomy

Vitreous surgery is now routinely undertaken for primary detachments especially in patients who have already had cataract surgery done previously. It is especially useful in cases when the tears are very large or placed very far back (posteriorly) on the retina, when there is a macular hole causing detachment, or if there is blood in the vitreous blocking a clear view of the retina. Success rates for these cases are much better with vitrectomy than with scleral buckling.

Occasionally, retinal detachment is so complicated and severe that it cannot be treated with either standard scleral buckling surgery or pneumatic retinopexy. Moreover scleral-buckling surgery fails approximately 5% to 10% of the time because excessive scar tissue grows on the surface of the retina. This scar tissue is very bad for the eye. It pulls on the retina, causing it to re-detach. Retinal re-detachment usually occurs four to eight weeks after the initial surgery. The vitreous pulls on the retina, detaching it from the back wall of the eye. The scar tissue also puckers the retina into stiff folds, like wrinkled aluminum foil. This condition is called proliferative vitreo-retinopathy (PVR).

The only way to unfold and re-attach the retina is to cut away the vitreous and remove the scar tissue with vitrectomy surgery and then re-attach the retina. The surgeon uses a fibre-optic light to illuminate the inside of the eye and a variety of instruments (scissors, forceps and laser probes). The vitreous gel is removed as well as abnormal scar tissue, and replaced with fluid or air. Sometimes the natural lens or a previously existing intraocular lens (IOL) may have to be removed if the case is complicated. The holes and tears are sealed with laser, and fluid under the retina is drained. At times, vitrectomy is combined with placement of a scleral buckle. Often air, gas or silicone oil is placed in the vitreous cavity to hold the retina in place. If silicone oil has been used, it has to be removed at a later date as a separate surgical procedure.

Removing the vitreous and especially the scar tissue from the surface of the retina is a delicate process that requires the surgeon to lift and peel strands of scar tissue away from the retina. The surgery may take many hours in severe cases.

If the retina is successfully re-attached, the eye will recover some sight, and blindness will have been prevented. However, the degree of vision that finally returns up to six months after successful surgery depends upon a number of factors. Unfortunately, success in re-attaching the retina (anatomic success) does not always translate into marked visual improvement (functional success). This is because of permanent damage to fine vision cells of the macula. In general, there is less visual return when the retina has been detached for a long duration, or there is a fibrous growth on the surface of the retina. It should be clearly understood that often the purpose of surgery for PVR is to give the patient an eye that would have some supporting vision and could serve as a “spare tyre”, if the other eye ever loses vision entirely.

Microincision Vitreous Surgery (MIVS) with smaller instrument size is the latest revolution in Vitreous surgery. The finer instrumentation allows one to perform technically complex steps with greater safety. This translates into better visual outcomes and faster healing and recovery for our patient. This technique allows us to safely operate closer to the retina for peeling of fine membranes from the surface of the retina.

We are one of the first institutions to use the latest CONSTELLATION VISION system for performing vitrectomy. This has enabled us to achieve much better surgical results especially in complex cases like Diabetic surgeries. Our Vitreoretinal OR boasts of the 3 leading visualization systems ie the OFFISS, the Resight and BIOM These enable the surgeons to get an excellent wide field view for safe and complete vitreous surgery, resulting in excellent visual and anatomical outcomes.

What are the complications of surgery?

Even though the surgery for retinal detachment is generally successful, certain complications can occur. They include drooping of the upper lid and double vision, which are temporary. Serious complications include infection, bleeding severe enough to interfere with vision, glaucoma and cataract formation. However, these complications are very infrequent. Retinal re-detachment is the most commonly occurring problem. If this occurs, your surgeon will discuss the chance that a re-operation will successfully re-attach the retina. It is important for the patient to know that surgery may fail due to complications, or simply due to the progressive nature of the retinal disease.

Request a call back

I agree to recieve more information regarding services and offers at shroff eye center via SMS and Email

Disclaimer

This is not medical advice. Your ophthalmologist will help you decide which procedure and lens is best suited for your eyes. Every patient and eye is different and thus the experience for every patient is variable.

All product and company names are trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective holders. Use of them does not imply any affiliation or endorsement by them.

By being on the website, your personal data is being processed for communication with you and providing services. We use cookies to collect and analyse information on site performance, usage, enhancement of customer usability and improvising the website. We have put in place terms of use,

By clicking on accept you agree to all the policies mentioned above. You can read more about them by clicking on read more and accept them individually.

Call us

Call us Email us

Email us